I don’t do what I do to instill fear. I do what I do to educate, so YOU can make informed choices for your family.

Published: May 31, 2020

This is an ad-free article.

To make a contribution to help us keep our most widely-read articles ad-free, click here. Thank you.

Is what I report on this website “fear-mongering?”

Yesterday an article was shared with me that mentioned me and my advocacy work. This article here, today on my website, is by way of a rebuttal — addressing not only a few misconceptions articulated in that particular piece, but also comments and critical reactions to my work that have appeared (and reappeared) over the years.

While, as I said, this post was not written only in response to yesterday’s article, the author of the piece contends that it is relatively useless to simply know whether or not something contains Lead. The allegation sounds reasonable enough at first glance: that simply knowing whether any particular example of a consumer good — even a plate, mug, bowl, or other dishware — “merely” contains Lead serves no function; that only if something has confirmed currently leachable/bioavailable Lead is that information of any value.

I emphatically disagree.

I actually believe the opposite. Simply knowing if something has Lead (Mercury, or Arsenic, etc.) puts consumers in a position of power in making choices for their families and the health of our environment.

Consumers have a right to know what they are buying — particularly if the items include neurotoxic elements.

I think all consumers have a right to know if the products they buy for their home (or use every day) “merely” contain Lead (Mercury, Arsenic, Cadmium, Antimony, or any other toxic heavy metals)! Moreover, leach-testing on every single item ever made would obviously be wildly cost-prohibitive, and as a practical matter would also be impossible — but knowing if a manufactured consumer item contains (or is likely to contain) Lead or other highly neurotoxic metals (using high-precision XRF technology) is a very important piece of information that families can use to make informed choices for their household.

The fact of the matter is that if we had advance knowledge that something contained 20,000 or 50,0000 — or even “only” 10,000 ppm Lead, most of us would likely choose to not purchase (or otherwise acquire) that particular item for use in our home. This is especially true if the item in question is something intended for food use, in our kitchens or dining rooms. That we (as humans) are likely to choose non-toxic options (over items with heavy metals) is even more likely when you consider how many non-toxic/Lead-free options are out there (and surprisingly, in most cases the Lead-free options are also often the least-expensive options!).

Giving people access to information regarding the historic (or current) use of toxicants in the manufacture of particular consumer goods does not, by default, automatically incite or encourage fear. I do acknowledge that some people are fearful — of many things. Some people are ignorant, misinformed, confused, or overwhelmed; others have been traumatized and may have developed (diagnosed or un-diagnosed) OCD over their fear of the toxicants in our world. That does not — must not — trump the importance of disclosing toxicants (still) widely used in the manufacturing of consumer products (or prevalent in family heirlooms we may use daily).

Few people are doing this work

Given no public agency is looking at many categories of these currently manufactured products commonly found in our homes, not to mention, vintage products, I contend the work I do is of value — because it provides specific information to families that no one else is providing (again — so they can make their own informed choices, based on scientifically replicable accurate data).

I am very careful with language in all of my posts and work hard at not indulging in sensational posts or click-bait headlines, nor any needlessly alarming, or exaggerated statements on my website. It is very important to me that the information I share is simple, factual, consistently science-based, and that all consumer goods test results reported are replicable.

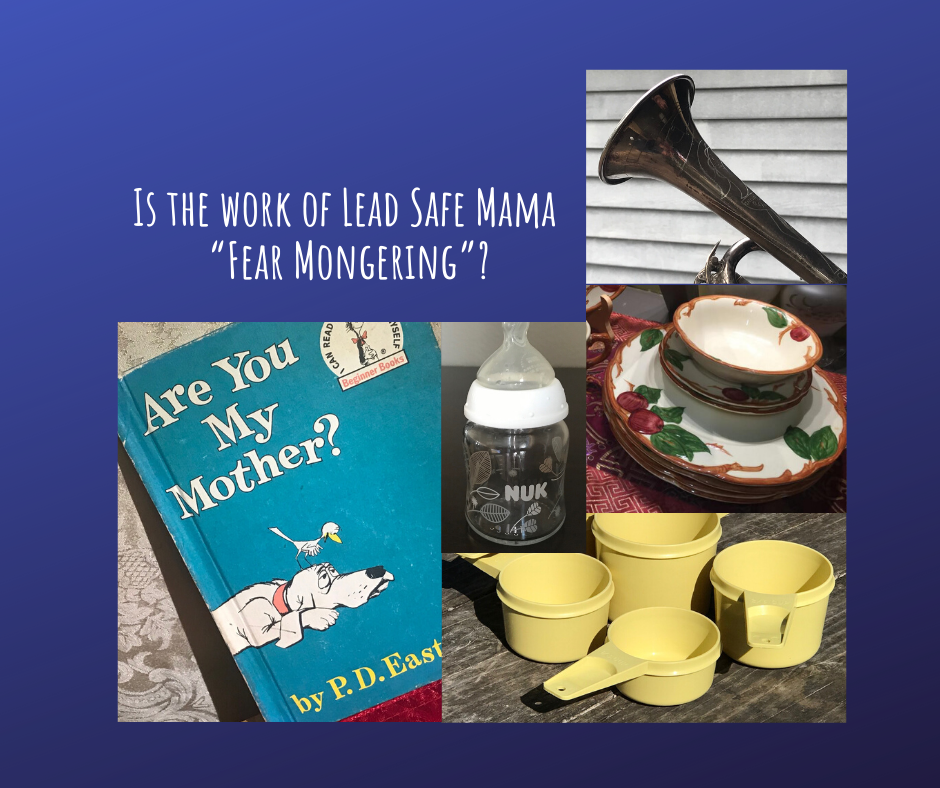

There are only a few specific types (or brands) of products that I consider inherently very unsafe (because of their function and usage in a typical home, and the risk of consequent possibly chronic) exposure to the toxicants used). In those few cases, I endeavor to be clear and explicit about my concerns with these products. (Some examples of more concerning products: all Franciscan Potteries china, colorful vintage Pyrex bowls, and pre-2010 Tupperware).

I am not fear-mongering

Most of my readers (this includes more than 1,948,000 readers in 2019 alone, from more than 200 countries) do not react to what I write with fear. Most read the words without “reading between the lines” (looking for, or making up, some kind of tacit meaning beyond my words) and most use the information provided to make informed choices.

Beyond any possible direct health risks or concerns (for the end user of any given product), there are also legitimate environmental issues surrounding the mining, refining, and use of toxic heavy metals in consumer products. But any “fear”/hysteria around this information is counter-productive and arises in the individual reader — in that person’s unintended interpretation or inappropriate response to the posting of the simple routine, factual scientific test results I publish (normally shared intentionally devoid of any emotional charge and always shared without baseless allegations or assertions).

Lead is incontrovertibly toxic — in extremely small amounts/at very low exposure levels. This is a fact.

If the presence of Lead were not inherently problematic at even very low levels, the information shared on this blog might arguably not be valuable or relevant information. However, the mere presence of any Lead in a child’s environment has been well-documented to be inherently problematic — at remarkably low levels (so low that after researchers reached the consensus there is no known “low threshold of toxicity” for Lead, our public health agencies in the U.S. and internationally eventually acknowledged this fact and officially, universally moved to include the language that “there is no safe level of Lead exposure”).

If you are blasé about newly-manufactured consumer goods that contain high levels of Lead (Leaded brass, Lead fishing weights, Lead crystal) then your focus is too narrow. If you don’t have any concern for Lead in products of these types at the levels typically found (because as of yet no one has “proven to you” the impact to the end user for these products), then you are obviously not looking at the bigger picture.

There’s a bigger picture here: the planet.

The bigger picture is the concern for the entire lifecycle of any product that incorporates high amounts of Lead — and the very real risks to many people all along the supply chain. This includes risks to the miners that mine the Lead (and other toxicants) for the raw materials for these products, risks to the workers that make the products, and perhaps most importantly — the impact on the human habitat. The larger environmental impacts range from highly toxic waste produced in the mining and refining of Lead to global pollution from emissions generated through manufacturing Leaded products, and ultimately including the issues created at the end-of-life for Lead-containing products with disposal (even the potential contamination of the manufacturing chain for recycled goods).

The world does not revolve simply around any one of us. If the air we breathe and the water we drink and the soil we grow our crops in are fundamentally contaminated with Lead from manufacturing, mining, refining, use, and reclaiming or disposal of Leaded products — we, as stewards of the Earth — bear responsibility for those contaminations, too.

“OCD” or not?

While the biggest human impact problem (when it comes to Lead) is, first-and-foremost Lead-contaminated dust in older housing and other buildings that were historically painted with Lead paint, being concerned about the very real additional presence and impact of Lead in consumer goods is not “OCD.”

If the still-largely-unstudied/undetermined specific impact of lower and lower levels of exposure were not a concern, public health agencies across the globe would not have set the toxicity level for Lead in consumer goods at 90 to 100 parts per million (ppm). Consumer goods have the potential to cause harm at very low levels. This is why these government standards have been set. However, it is well beyond the capacity of any government to test all things for safety.

In the absence of the government testing of all things, just because something has not yet been proven to be harmful does not mean it is safe. And thus people like me play a role in nudging scientific research and public policy along in the right direction, shifting public concern in a way that encourages scientists to do further study. To wit — years after activists (including me) began testing and reporting unsafe levels of Lead in coffee mugs — a formal study was done concluding this was actually a problem. Years after activists (including me) began reporting unsafe levels of Lead in vintage plastic toys, two formal studies were undertaken, concluding this was actually a problem. Years after activists (including me) began reporting unsafe levels of Lead in the painted decorations of functional (relatively modern) glassware, a study was done (in England) concluding this was actually a problem. I am actually just about to publish some new groundbreaking findings about Lead in vintage books and I expect these findings (which are scientifically replicable) will likely precipitate further study by a scientific body. (I will post that link here as soon as it is published).

Someone has to start the conversation

To those cynics who may be resistant of accepting “new” scientific information — tending to remain highly skeptical until such information is widely acknowledged at a cultural level: in every field, there must be early pioneers.

Just because someone is a pioneer in reporting seemingly new facts or new concerns does not invalidate those concerns (just be patient, there’s always a lag between a first discovery, subsequent related scientific findings, and popular knowledge). Let’s see how the timeline plays out with my new findings around vintage books!

Learning about Lead in household goods is a great introduction (to the larger Lead issue) for new moms

In addition to all of the above considerations, some conversations (like the concern for Lead in dishware) happen to be a great introduction to the subject of the concerns for Lead in our environment (overall). Everyone has dishes. Everyone also has (or had) a mother and a grandmother — and therefore everyone (or nearly everyone) has had interaction with potentially high-Lead dishes from past generations.

While I have worked with many families who were actually poisoned by their toxic dishes, in the scope of things, I don’t in fact see this as a primary threat (statistically, relative to other sources of Lead exposure) but I do see the topic of Lead in consumer goods as an impactful “gateway “/introduction for young families to learn the concerns for Lead exposure as it relates to them and their lives (especially impactful for young parents who have not previously thought of Lead-poisoning as potentially “their” problem).

If parents become aware of the potential for Lead in their dishes (whether or not their dishes might contribute to a child’s specific blood Lead level), they may get their child tested. If their child is tested and is negative for Lead, great! If their child gets tested and is positive for Lead in their blood, the parents will likely start looking around their home for other exposure sources (including sources of Lead dust from deteriorating paint). With the limited resources available today to combat childhood Lead poisoning, anything encouraging an increase in childhood blood Lead testing is a step forward.

Young parents don’t want to think of their house as toxic. It is too confronting.

Most families are reluctant to explore the potential concern of Lead paint in their homes. The financial liability of that inquiry is too much to bear, both in the short and long term. However examining the concern for Lead in consumer goods is a manageable task (dishes, to continue the example above, are inexpensive and easy to replace with modern Lead-free alternatives). Exploring the concern for Lead in consumer goods is a path to helping families discover an issue (and learn how it may or may not relate to their family) in a way that is less confronting (and less expensive) than testing their entire home — therefore it has value.

Lead is everyone’s problem — and the age-old conundrum is: how do we get everyone to see this? We are fighting against more than a century of marketing efforts by the Lead industry — marketing efforts designed to make us numb to the concern for Lead; marketing efforts specifically designed to make us think “this is not my problem, this is someone else’s problem.” By introducing people to the FACT that there is Lead in their dishware, you are opening their minds to the FACT that this is everyone’s problem and we all should consider the value of getting Lead out of our homes and environments.

But some Lead is useful in consumer products, right?

I disagree with this assertion 100%.

As Dr. Mark Pokras says in my film, I wish we could create legislation that says “Thou shalt not use Lead in anything, period!” It is 2020. Today, we have alternatives for every application in which Lead was previously used. Uses like Lead in car batteries are now roughly 100 years old, and there is no reason we should continue this practice. Car batteries absolutely DO poison the planet — the Lead in car batteries is neither unavoidable nor safe. While it is oft-cited as the most “recyclable” source of Lead (and I understand the Lead mining industry considers the recoverability/reusability of the Lead in car batteries to be a problem that needs to be addressed!) it is not ultimately a necessary use of Lead and there are still grave environmental implications with the use of Lead in this way.

In conclusion

In the meantime, (to those who are dismissing/mischaracterizing my work as “fear-mongering”), please stop trying to invalidate the work of honest, hard-working advocates simply trying to inform families so they can make intelligent choices for their families — choices not based on double-speak and marketing language provided by manufactures, but on data and facts and numbers.

Just because the long-term human implications of something have not yet been well-studied — like what happens to someone’s body if they “only drink out of Leaded crystal every now and then,” or if they drink “really quickly when they do” (two actual “objections” to my recommendation of avoiding ever drinking from Leaded crystal) — why would you risk putting one of the most neurotoxic substances known to man up against your lips when you can buy a Lead-free alternative for one dollar?! *

Thank you for reading.

Tamara Rubin

#LeadSafeMama

*Here’s an example of a wine glass on Amazon for about $2.50 per glass. While I have not tested this exact glass, it is advertised as Lead-free. Check out any Dollar Store, Walgreens, or similar shop for a $1 per glass version!

Amazon links are affiliate links. If you purchase something after clicking on one of my links I may receive a small percentage of what you spend at no extra cost to you.

For those new to this website:

Tamara Rubin is a multiple-federal-award-winning independent advocate for childhood Lead poisoning prevention and consumer goods safety, and a documentary filmmaker. She is also a mother of Lead-poisoned children (two of her sons were acutely Lead-poisoned in 2005). Since 2009, Tamara has been using XRF technology (a scientific method used by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission) to test consumer goods for toxicants (specifically heavy metals — including Lead, Cadmium, Mercury, Antimony, and Arsenic). All test results reported on this website are science-based, accurate, and replicable. Items are tested multiple times to confirm the test results for each component tested. Tamara’s work was featured in Consumer Reports Magazine in February of 2023 (March 2023 print edition).

Never Miss an Important Article Again!

Join our Email List

Hi Tamara,

Do you have any metal loafpan recommendations?

I appreciate your work! You can’t fix what you don’t know. As I learn from you, I have been able to replace, and make better buying choices for our household. I am appalled at the “bad stuff” out there in things we use daily. I am most definitely grateful for the knowledge.

Are you working with Consumer Reports at all? I think you should be connecting with them and they should be reporting what you have done.

Thanks.

Well stated, Tamara! I agree with you 100% and appreciate your work very much. I wish I learned this when I was younger.

Thank you for commenting!

Thank you for your tremendous dedication!

A Mother & Grandmother